Since the Second World War, gross world product has multiplied nearly 20-fold. This increase has two components: a 3.5-fold increase in the human population and a 5.5-fold increase in the global average income.

This enormous economic growth has come with heavy burdens on our planet: its limited natural resources are depleted, its regenerative capacities are diminished, and its soil, air, and water are getting polluted. Pollution includes climate-changing emissions of greenhouse gases such as CO2, CH4, N2O, SF6, and NF3, other anthropogenic pollutants such as particulate matter (PM2.5) in the atmosphere, heavy metals (mercury, cadmium, lead, arsenic) and plastics accumulating in soil, water, and food, persistent organic pollutants (such as DDT, PCBs, dioxins, furans), as well as many other harmful industrial chemicals (PAHs, VOCs, phthalates), pesticides, and herbicides. In all these ways, human activities are rapidly degrading our natural environment and climate, thereby triggering large present and future losses in human health and biodiversity. To illustrate the magnitude of these losses: air pollution from the burning of fossil fuels is estimated to have caused 8.7 million deaths in 2018, about 1/7 of all human deaths, mainly by increasing the incidence of respiratory ailments, heart disease, stroke, and cancer (Vohra et al. 2021; cf. Roser 2021).

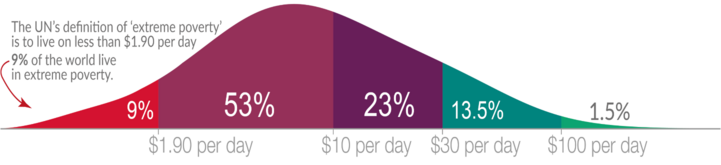

The enormous economic growth and its accompanying burdens have not been equally distributed. If the incomes of the world’s poorest segments had increased 5.5-fold along with the global average income, then severe poverty would now be history. Instead, roughly half of all human beings are suffering one or more severe deprivations, such as an inability to afford a healthy diet (FAO et al. 2024, 29), a quarter are just barely surviving with their health seriously compromised, and millions die prematurely each year from poverty-related causes.

*

Global income distribution in 2022, from Our World in Data, denominated in “international dollars,” representing what can be bought with one US-dollar in the United States. Only about 6% of human beings have the global average income or more while around 40% live on less than one-tenth of the average income.

*

On the other hand, the global poor do get more than their fair share of the burdens of ecological degradation as they are far less able to avoid or to protect themselves against extreme weather events (such as unbearable heat), “natural” disasters, shortages of food and water, expanding tropical diseases, and sea level rise with salination of ground water.

Natural justice suggests that beneficiaries from activities that have gravely harmed others should share some of their benefits with those whom these activities have been harming. But under present international law, whose formulation was dominated by the powerful North Atlantic states, no such compensation is owed: industrialized countries are free to impose ecological externalities on other peoples without limits, liabilities, or penalties.

Present international law does however require a payment stream in the opposite direction. If poorer populations seek ecologically responsible development, they must pay monopoly rents for using green technologies that have been developed and patented by Northern innovators who, thanks to their huge superiority in financial and human capital, enjoy a crushing advantage in the innovation race. Under the TRIPS Agreement, Southern populations are required to enforce patents and hence to pay for permission to deal with the ecological mess that predominantly originates in the global North (World Trade Organization 2005, articles 27, 28, 33).

At COP 15, Copenhagen 2009, 23 rich Western (“Annex-II”) countries reluctantly agreed to “mobilize” for the global South some international climate finance (ICF), which was to reach $100 billion annually by 2020. The OECD declared this promise belatedly fulfilled in 2022, when the mobilized amount reportedly reached $115.9 billion. At COP 29, Azerbaijan 2024, a new commitment was made to increase ICF to $300 billion annually by 2035.

It has been widely criticized that these amounts are dwarfed by the costs that climate change is imposing in the global South, which are estimated at $2.4 trillion annually (Grantham Research Institute 2024). But the problems go deeper. As Oxfam has shown, based on OECD data, about two-thirds of what is counted as climate finance consists of loans that increase the already highly excessive debt burdens of poor countries (Oxfam 2023, 6). Moreover, climate finance can also count as official development assistance (ODA) — even loans if granted on favorable terms. As a result, richer countries often meet their ICF commitments cost-free by simply shifting their ODA toward environmental projects. According to a CARE report, donor countries count 93% of the funds they declare as ICF also as ODA (CARE 2023). In this way, the $116 billion counted in 2022 as ICF and the $211 billion for ODA add up to a mere $219 billion.

One final problem is that the official tracking of ICF focuses exclusively on how much is spent or (more often) lent, without regard to impact. This sort of accounting undermines the effectiveness of ICF by allowing decision-makers to sideline the goal of effectiveness in favor of their other policy goals — for example, the goals of creating jobs or serving powerful corporations in the donor country.

There has been much excitement about the new Trump Administration’s decision that the US will no longer care about poverty abroad — a decision that other Western countries have quickly followed with cutbacks of their own. Trump’s decision is indeed having dramatic effects by undercutting the work of multilateral organizations such as the World Food Program, the World Health Organization, the Global Fund, the Gavi Vaccine Alliance, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the United Nations Population Fund, and the International Organization for Migration. But Trump’s cuts will have little effect on the poorer countries’ capacity to reduce ecological harm because ICF was mostly smoke and mirrors anyway. Trump’s policies do, however, aggravate ecological harm around the world by perversely rolling back environmental protections, impeding the spread of green technologies, and supporting fossil fuel extraction and consumption.

A bright ray of hope in this darkening picture is China. Chinese innovators have made extraordinary contributions to green innovation, accounting for 58.2% of all green and low-carbon patent applications filed for the first time in the 2016-22 period (CNIPA 2023, 5). There is also rapid uptake of such green technologies in China, as exemplified by the fact that about 40% of new cars sold there are now electric (versus under 10% in the United States). On the strength of this impressive record, empowered by the withdrawal of the United States from its ecological responsibilities, and deeply sympathetic to the injustices suffered by the developing world, China has the standing and the capacity to lead the global fight to contain ecological degradation. With Chinese leadership, humanity can still win this fight by developing and implementing the right impact-oriented mechanisms for encouraging the rapid development and dissemination of highly effective green technologies. Such a path is encouraged by Chinese President Xi Jinping: “Harmony between man and nature is a defining feature of Chinese modernization, and China is a steadfast actor and major contributor in promoting global green development. … However the world may change, China will not slow down its climate actions, will not reduce its support for international cooperation, and will not cease its efforts to build a community with a shared future for humankind” (He Yin 2025).

*

A Chinese version of this article, titled 富国一边向穷国转嫁生态成本,一边收取“绿色高利贷”, is available at https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/O5Pr-pCAV_hmUbxQN6IebQ.

*

References:

CARE, “Double-counted Climate Finance Means Poorest Pay the Price,” September 18, 2023. https://careclimatechange.org/double-counted-climate-finance-meanspoorest-pay-the-price

CNIPA (China National Intellectual Property Administration). 2024. 2023 Report on Statistical Analysis of Green and Low-carbon Technology Patents Worldwide. https://english.cnipa.gov.cn/art/2023/7/6/art_3262_186148.html.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2024. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 – Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. FAO. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4060/cd1254en

Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. 2024. “New Report Recommends COP29 Negotiations on Climate Finance Should Focus on Mobilising $1 Trillion per Year for Developing Countries by 2030,” London School of Economics and Political Science, November 14. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/news/new-report-recommends-cop29-negotiations-on-climate-finance-should-focus-on-mobilising-1-trillion-per-year-for-developing-countries-by-2030.

Oxfam. 2023. “Climate Finance Shadow Report 2023: Assessing the delivery of the $100 billion commitment,” June. https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621500/bp-climate-finance-shadow-report-050623-en.pdf

He Yin. 2025. “China is a Steadfast Actor in Promoting Global Green Development.” People’s Daily, May 6. https://en.people.cn/n3/2025/0506/c90000-20310727.html

Roser, Max. 2021. “Data Review: How Many People Die from Air Pollution?,” Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/data-review-air-pollution-deaths.

Vohra, Karn, Alina Vodonos, Joel Schwartz, Eloise A. Marais, Melissa P. Sulprizio, & Loretta J. Mickley. 2021. “Global Mortality from Outdoor Fine Particle Pollution Generated by Fossil Fuel Combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem,” Environmental Research 195, 110754, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0013935121000487.

World Trade Organization. 2005. Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights as Amended by the 2005 Protocol Amending the TRIPS Agreement. Annex 1C. Geneva. https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/trips_e.htm.